Quick takeaways on New York City Urbanism from Nicole Gelinas

Last year, Nicole published the Bible on New York City streets and transit

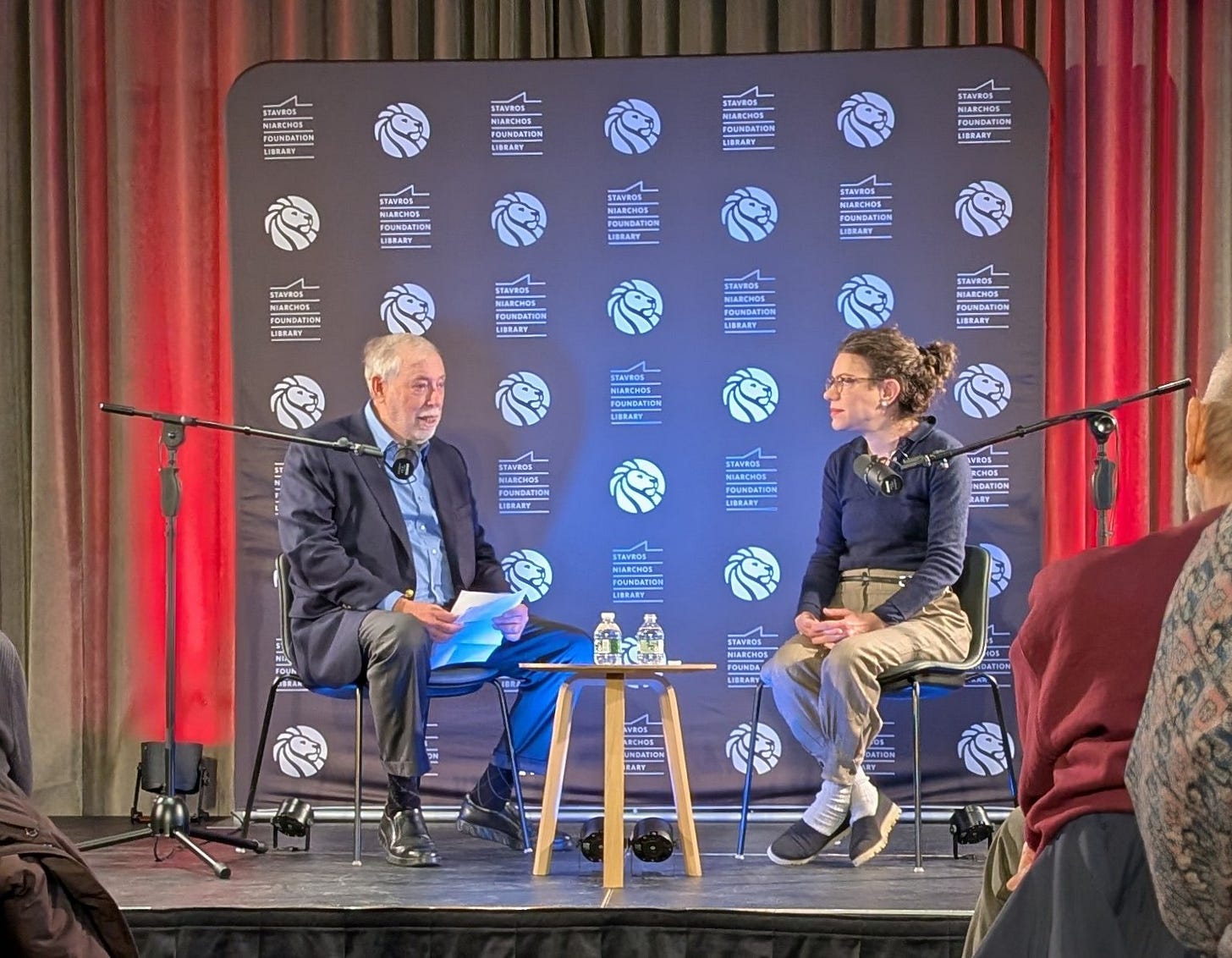

Right now I am working through Nicole Gelinas’s 450-page tome on New York City’s relationship with cars and transit, Movement: New York's Long War to Take Back Its Streets from the Car. I haven’t finished yet, but today I had the chance to hear from Gelinas in a conversation with 'Gridlock' Sam Schwartz (a former Traffic Commissioner who has been working on New York City’s Congestion Pricing plans for 50 years).

I’ll post a full book review another time but I wanted to share some highlights from the conversation and audience Q&A:

Rethinking historical narratives

Now that The Power Broker is 50 years old, we can look back and acknowledge that we probably focus too much on blaming Robert Moses for the car-centric urban planning the city embraced between WWI and the 1960s. Often, Moses was just implementing the plans other civic organizations had already drawn out.

Similarly, we praise Jane Jacobs for taking down Moses but should give more credit to her predecessor Shirley Hayes for dealing Moses his first major loss in the 50s: getting cars out of Washington Square Park. This took many years and lots of signatures.

Turning points for transit

The Transit Strike of 1966, ironically, helped save public transit. It showed that the city couldn’t rely on cars to get commuters in and out of Manhattan in a timely manner. It help cement arguments to use surpluses from bridges to fund public transit.

The pandemic revealed the good and the bad of New York City’s transportation systems. It strongly validated Mayor Bloomberg’s choice to expand bike lanes and public plazas (good). It also revealed that our ability to tackle crime in the subway wasn’t as robust as expected (bad). It has basically taken 5 years and multiple mayors to revert back to pre-pandemic levels of crime in the subways.

The build-out of bikes lanes in New York City has slowed down during the DeBlasio and Adams administrations after a quick start during the Bloomberg years. Part of the problem today is that bike lanes are seen as an anti-Trump policy idea, but that means it is politically costly.

New York City streets today (and tomorrow)

Congestion Pricing works. This is pretty clear whether it’s just an eye-ball test walking outside or if you look at the number of vehicles entering lower Manhattan (it’s about 9% lower than the projection otherwise). That said, people dislike the idea of being charged more to drive to Lower Manhattan, which is why President Trump has latched on to Congestion Pricing as a wedge issue.

We probably need some form of registration for food delivery drivers (“Deliveristas”). The problem is that motorized vehicles in bike lanes and sidewalks drive away and annoy (if not endanger) pedestrians and bikers.

About 20% of people who ride the subways today do not pay a fare (i.e. fare theft). Interestingly, the city had the exact same problem in the early 90s and used stricter enforcement (like community service for first time offenders) to cut down on the problem. Right now you need to get caught multiple times for actual action to be taken against you.

Also, buses were free for a year during the pandemic and many riders never resumed paying.

If we enforced noise regulations better (like London does), we could relax our new, complex bureaucracy around outdoor dining.

We will need to act proactively for autonomous vehicles to not cause congestion and traffic in the city. This is definitely a possibility in the worst case scenario. The city did not do a good job regulating Ubers and Lyfts when they first appeared.

Other opportunities

We haven’t built a bridge to Lower Manhattan in over a century. Sam Schwartz thinks a bike + pedestrian bridge from LIC to Roosevelt Island to Lower Manhattan could make sense.

For environmental review reform, a good idea is capping the time any stage of the review process takes. Often, the problem is not the regulation per se but politicians using the regulation as a way to “run the clock” on projects that require political capital to actually complete or start (since redirecting capital means deprioritizing other projects).

Simply getting rid of the regulation won’t lead to more transit or housing being built — you still have to actively advocate for it. Just getting rid of environmental regulations might just lead to more coal mines, as Gelinas put it.