Everything you missed about New York’s Cash Bail Reforms

Years of rollbacks have left reforms in a piecemeal state. Focusing on better data and speedier trials could satisfy both sides of the debate.

Author’s note: I recently completed a course on New York government and wanted to share what I learned about the state’s Cash Bail reform over the past five years. Reducing the amount of time people spend in jail and residents feeling safe in their daily lives are both parts of achieving Abundance in New York City.

Before we talk about Bail reform in New York, let’s define what bail is and its role in American criminal procedure:

What is Bail?

Although the specifics of criminal procedure vary state-to-state, here’s how it typically plays out (emphasis mine on where bail appears):

As you can see, bail is just one step in a complicated process. In fact, it is not one of the controversial steps in American criminal procedure. In the book Law 101 by legal scholar Jay Feinman, bail is only mentioned in passing in a 53-page chapter on criminal procedure. In contrast, topics like the death penalty and sentencing guidelines receive their own multi-paragraph sections.

What is the Bail Reform movement?

I personally think of the Bail Reform movement as a subset of the Prison Abolition and Decarceration movements with some real wins in the 2010s. For example, in 2017 New Jersey eliminated cash bail and saw jail populations drop by about 30 percent without much public backlash.

In New York, the movement to abolish cash bail gained steam due to the story of Kalief Browder. As a teenager from the Bronx, Browder spent three years in jail on Rikers Island since his family could not pay a $3,000 cash bail. His charges were eventually dropped due to a lack of evidence. In brutal ending to his story, he committed suicide in 2015 at the age of 22.

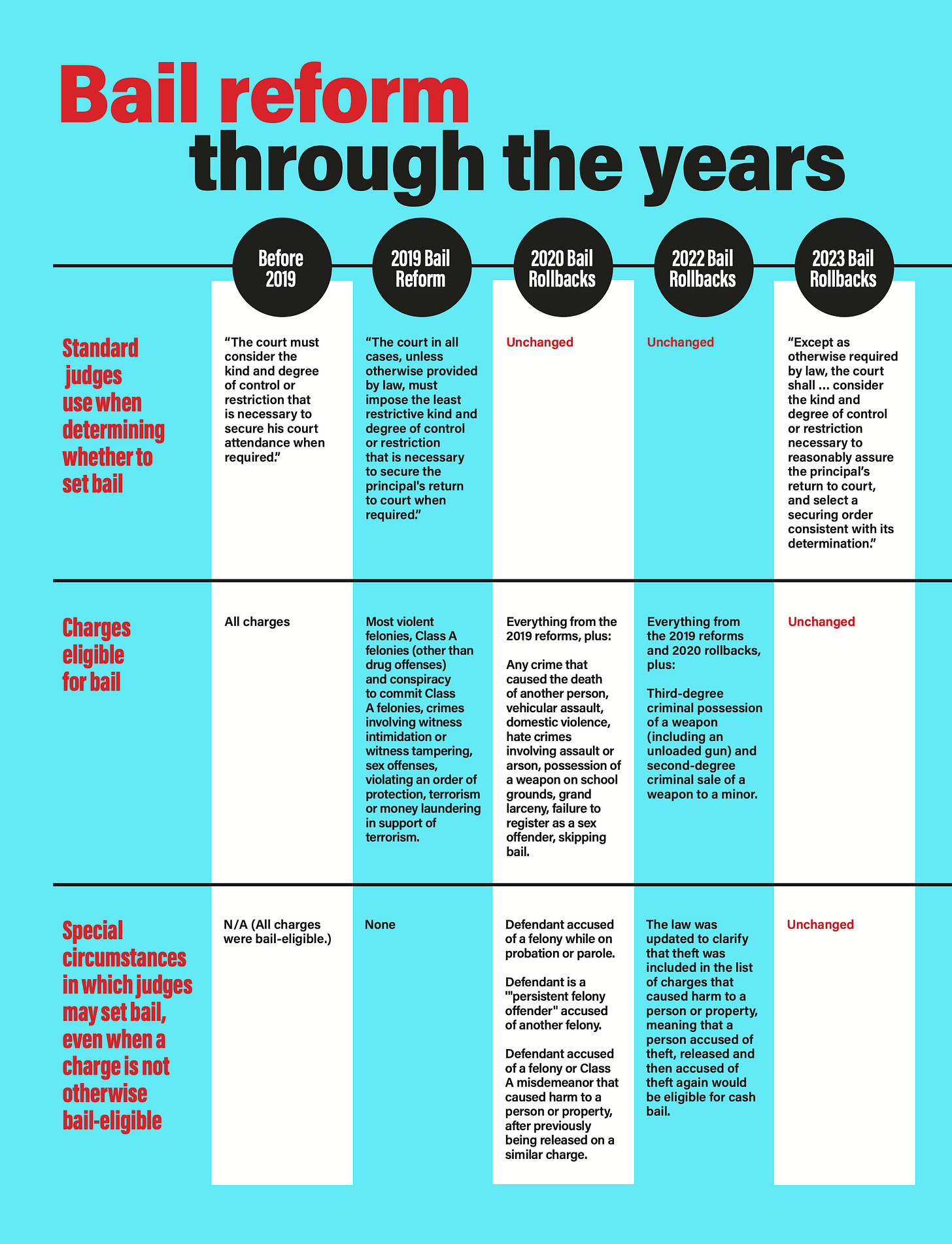

New York’s 2019 Bail Reform Law

This law (Section JJJ of S.1509-C / A.2009-C) eliminated cash bail for most misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies. Instead, the law instructs judges to consider requiring “the least restrictive conditions” that will get the defendant to return for future hearings or trial. The law emphasizes releasing the defendant under “non-monetary conditions” instead of cash bail. For example, judges could require electronic monitoring of the defendant’s location instead of using bail to compel the defendant to return for future hearings.

The (fast) backlash to Bail Reform

Unlike judges in other states that passed bail reform in the 2010s, New York judges are not supposed to consider the threat to public safety when making the decision to send someone to jail or set bail (New York's Legislature banned using “dangerousness”in 1970). Instead, judges are only supposed to look at information that helps predict if the accused will reappear in court for future hearings.

Explaining this nuance to New Yorkers can be difficult. People get angry when they see judges releasing violent criminals with the “the least restrictive conditions” needed to get them to reappear in court. For example, in late 2019 police arrested a woman twice in three days for slapping and yelling at Jewish victims. A judge then released her without bail, which caught press attention. It immediately added pressure to rollback the bail reforms about to take effect.

Bail Reform Rollbacks over the years

Starting in 2020 the state legislature began passing laws that increased the number of crimes that were eligible for cash bail and gave judges more leeway in justifying conditions to get the accused to reappear in court:

2020 Rollbacks (Part UU of S.7506-B / A. 9506-B): this law made it more clear how defendants should behave if judges release them on non-monetary conditions. For example, they should make a good-faith effort to have a job or be in school. It also added crimes like terrorist money laundering as bail-eligible. It also required the chief administrator of the courts to release data about pretrial release and detention.

2022 Rollbacks (Subpart B of S. 8006-C / A. 9006-C): this law added crimes like having a weapon on school grounds and hate crimes as bail-eligible. It also opened the door to using "dangerousness" again. For example, judges could now consider the defendant’s use of guns. It also added new dimensions of data for the courts to record and release. The data should mention if the prosecutor asked for bail, and what the court ended up deciding.

2023 Rollbacks (Part VV of S.4006-C / A. 3006-C): this law states that instead of always requiring the "least restrictive" conditions, judges can view each case as unique when justifying their decisions. It also makes it easier for judges to impose both bail and a non-monetary condition.

Where Bail Reform Rollbacks go from here

In the near-term, rollback bills continue to focus on making certain crimes bail-eligible. For example, Long Island Republicans have introduced a bill to make body dismemberment or hiding a human corpse bail-eligible. This came after people arrested for a weird crime involving body parts scattered in a park did not face bail. Instead, a judge released them with electronic location monitors.

What I suspect about Cash Bail politics

I get the sense that Bail Reform rollback supporters might not actually want bail reforms to be fully rolled back and leave the headlines. Instead, they know that this issue is politically useful since they can blame crime on it and pass bills modifying it.

Instead, the public could demand alternative proposals that reduce jail populations without sacrificing public safety.

Alternative policy ideas to safely reduce New York’s jail population

I think reasonable proposals include:

End cash bail but add dangerousness as a detainment criteria: New York is the only state that doesn’t have judges consider threat to the public when deciding if to detain a defendant while waiting for trial or hearings. Sure enough, Assembly Bill A4208 would add this criteria. It is currently in Committee.

Set targets for shorter pre-trial detention lengths:Bail would be less of an issue if the time between arraignment and trial was very short. As mentioned in the laws above, the New York court system should be releasing reports on pre-trial detention metrics and trends. Indeed, I was able to find a dataset on Rikers Island’s jail population. Metric targets could focus the conversation on how to reduce jail populations and help the public understand what laws work.

Add judges and public defenders for speedier trials: If we increased the throughput of the court system, we wouldn’t need as much pre-trial detention since the time to get to trial would be shorter. We could do this by adding more judges and public defenders. I could not find any bills on this topic, so more education and research might be needed here. But on the surface, this idea seems under-discussed and an opportunity for both sides to claim a victory on Bail Reform.